Chapter 2

The Era of the Sophia House Men’s Dormitory

As Japan’s rapid economic growth brought stability to the society, the number of students entering Sophia increased and the demand for places in the dormitory grew accordingly. In response, the university decided to erect new buildings on campus in place of those which were burned down during the war. In 1956, Sophia House (Jōchi Kaikan), which housed a new male student dormitory, was completed. Residents of the new dormitory participated in its management under the guidance of dormitory supervisors (* Besides the male student dormitory, the building also housed a dining hall and a campus store). Internationalization of college education eventually brought new changes to the dormitory. An OECD education mission which visited Japan in 1970 suggested that Japan as a member of the international community should take a more active role in international educational cooperation. The Central Council for Education, an advisory body to the Minister of Education, subsequently issued various recommendations regarding internationalization of education. Based on these, the Council for International Student Policy toward the Twenty-First Century, another government advisory body, submitted its “Proposal on International Student Policy toward the Twenty-First Century” in 1983. This proposal, which aimed to increase the number of foreign students in Japan to 100,000 by the beginning of the twenty-first century, was an epoch-making proposal in the history of Japan’s policy on international students. Meanwhile, Sophia University introduced in 1971 an admissions system for foreign students wishing to study in Japan, ahead of other Japanese universities. This chapter introduces the life of students living in the student dormitory between 1956 and the late 1980s, from the opening of Sophia House to the period when the university sought to further strengthen its international character.

1. Completion of Sophia House

Document Number:Album_3_17_5_P.44

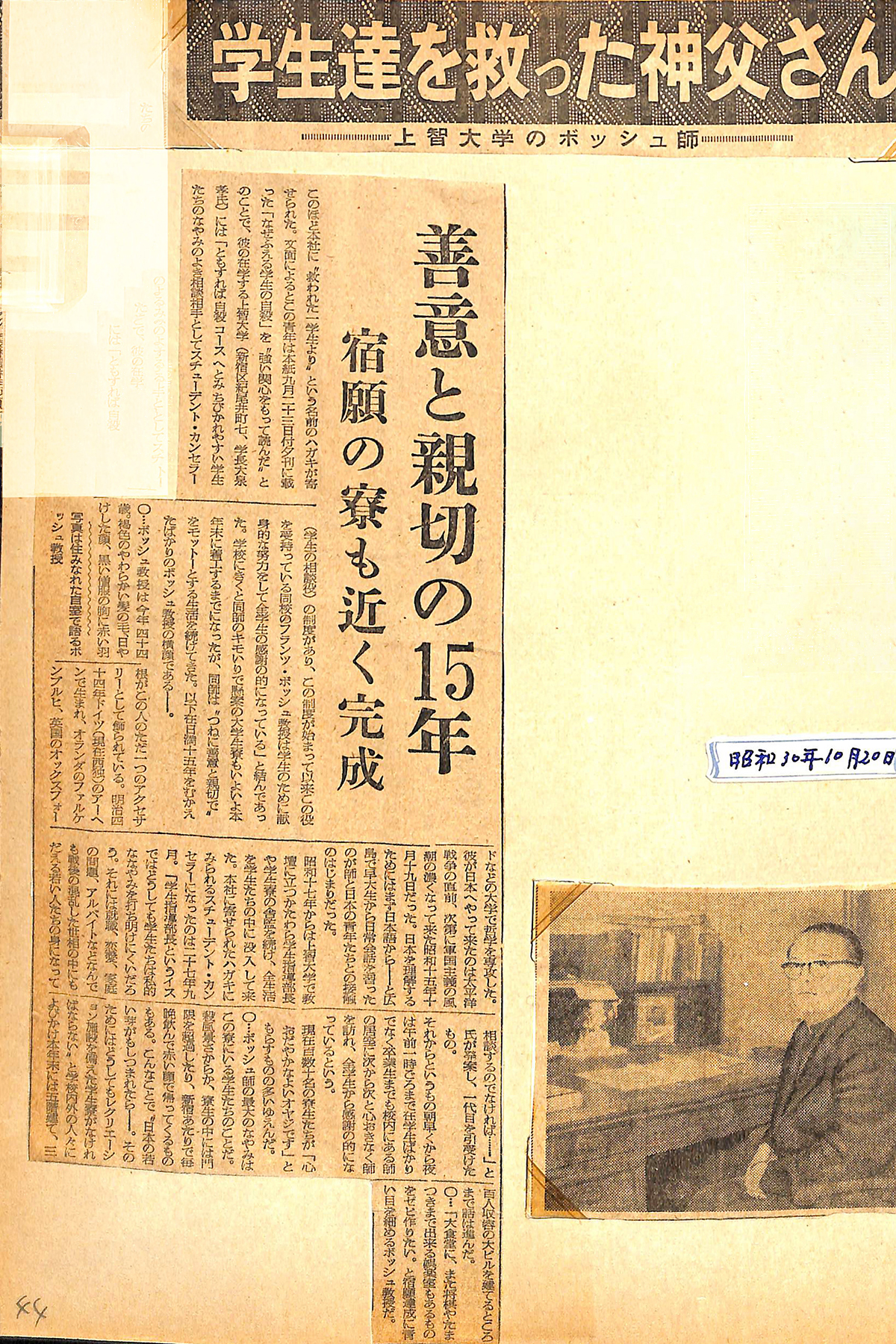

A scrap of an article reporting on Father Bosch’s efforts to build the Sophia House men’s dormitory, published in the Nihon Keizai Shimbun newspaper on October 20, 1955 (from Father Bosch’s personal album)

Document Number:Album_3_17_5_P.44

A scrap of an article reporting on Father Bosch’s efforts to build the Sophia House men’s dormitory, published in the Nihon Keizai Shimbun newspaper on October 20, 1955 (from Father Bosch’s personal album)

It was Father Bosch, the head dormitory supervisor at that time, who took the leading role in building a new dormitory for students living in the Bosch Town Quonset huts. The article from the Nihon Keizai Shimbun newspaper shown on the left introduces Father Bosch’s activities as a student counselor. With respect to the new student dormitory, he was quoted as saying, “we would really like to build [a facility] which includes a large dining hall as well as an amusement room where [students] can play Japanese chess (shōgi) and billiards.”

Document Number:Album_3_17_6_P.12

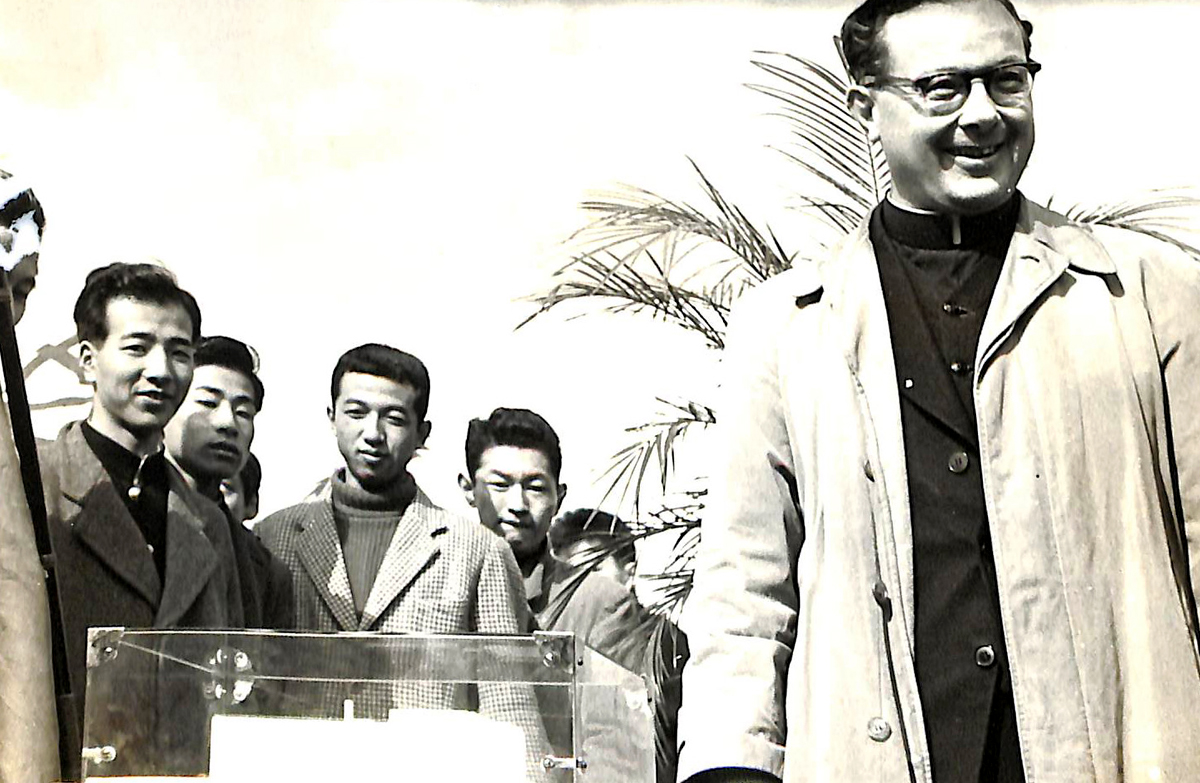

Father Bosch and students look at a scale model of Sophia House.

Document Number:Album_3_17_6_P.12

Father Bosch and students look at a scale model of Sophia House.

Document Number:nega 1_0613

At the left rear is Sophia House under construction (1955). The Quonset huts are in the foreground, with Building No. 1 visible in the background, while the old Building No. 2 is in the middle foreground to the right.

Document Number:nega 1_0613

At the left rear is Sophia House under construction (1955). The Quonset huts are in the foreground, with Building No. 1 visible in the background, while the old Building No. 2 is in the middle foreground to the right.

Document Number:nega 1_0303

Blessing ceremony conducted in the lobby on the ground floor of Sophia House (1956)

Document Number:nega 1_0303

Blessing ceremony conducted in the lobby on the ground floor of Sophia House (1956)

Document Number:100 Years of Sophia_P.63_1

Sophia House, completed in December 1956 (demolished in 2006), seen from the direction of the campus “Main Street,” looking toward the East Gate

Document Number:100 Years of Sophia_P.63_1

Sophia House, completed in December 1956 (demolished in 2006), seen from the direction of the campus “Main Street,” looking toward the East Gate

The new men’s dormitory set up inside Sophia House soon became a place for social gathering, as students living in Bosch Town dormitory huts and St. Aloysius Hall moved in.

Document Number:『Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun (The Sophia Times)』No.104

December 15, 1958 issue of Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun (The Sophia Times), the student newspaper

Document Number:『Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun (The Sophia Times)』No.104

December 15, 1958 issue of Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun (The Sophia Times), the student newspaper

“The roaring sound that awakens us comes from the engine of Big Buddy’s motorcycle. Though it makes a horrible sound, it is a foreign import, made in Germany.”

[A short song sung by dormitory students]

“Big Buddy was always pranked on April fool’s day.”

[An episode told by dormitory students]

Father Bosch, who was affectionately known to students as the “Big Buddy” (oyaji, an affectionate term to call one’s father), suddenly passed away on November 28, 1958. On the left is an edition of the student newspaper Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun (The Sophia Times) issued a month after Father Bosch’s death. Many humorous and heartwarming episodes about him were introduced in this edition of the newspaper, and also in the booklet published to mark the tenth anniversary of the new student dormitory.

2. Student Life in the Sophia House Men’s Dormitory

The new men’s dormitory was run by a self-government body formed by the residents, under the guidance of the dormitory supervisors, many of whom were Jesuit priests. The residents not only made dormitory rules, but also engaged in various activities such as social gatherings with residents of Sophia’s female student dormitories (Meisen women’s dormitory and Enoki women’s dormitory), the dormitory festival, and commemoration of major dormitory anniversaries. The spirit of resident self-government made the student dormitory a rather special place within the University, especially during and after the time of student activism in the 1960s and 1970s. The photos below provide us with some vivid images of the life of students at the men’s dormitory during those years.

Document Number:100 Years of Sophia_P.63_2

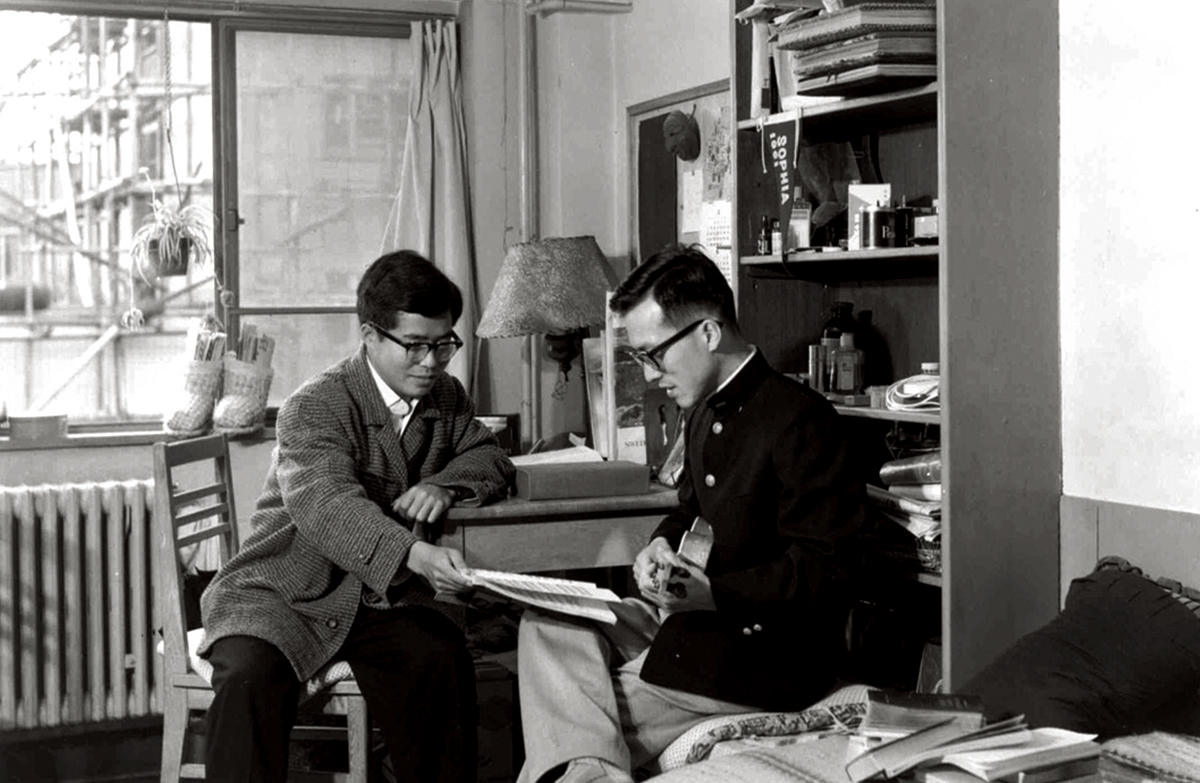

A room in the Sophia House men’s dormitory

Document Number:100 Years of Sophia_P.63_2

A room in the Sophia House men’s dormitory

Document Number:100 Years of Sophia_P.63_3

Father Bosch and residents enjoying a Christmas party at the men’s dormitory

Document Number:100 Years of Sophia_P.63_3

Father Bosch and residents enjoying a Christmas party at the men’s dormitory

Document Number: Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

Dormitory Festival

Document Number: Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

Dormitory Festival

Document Number: Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

A dormitory dance party

Document Number: Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

A dormitory dance party

Document Number:donated by a former resident_13

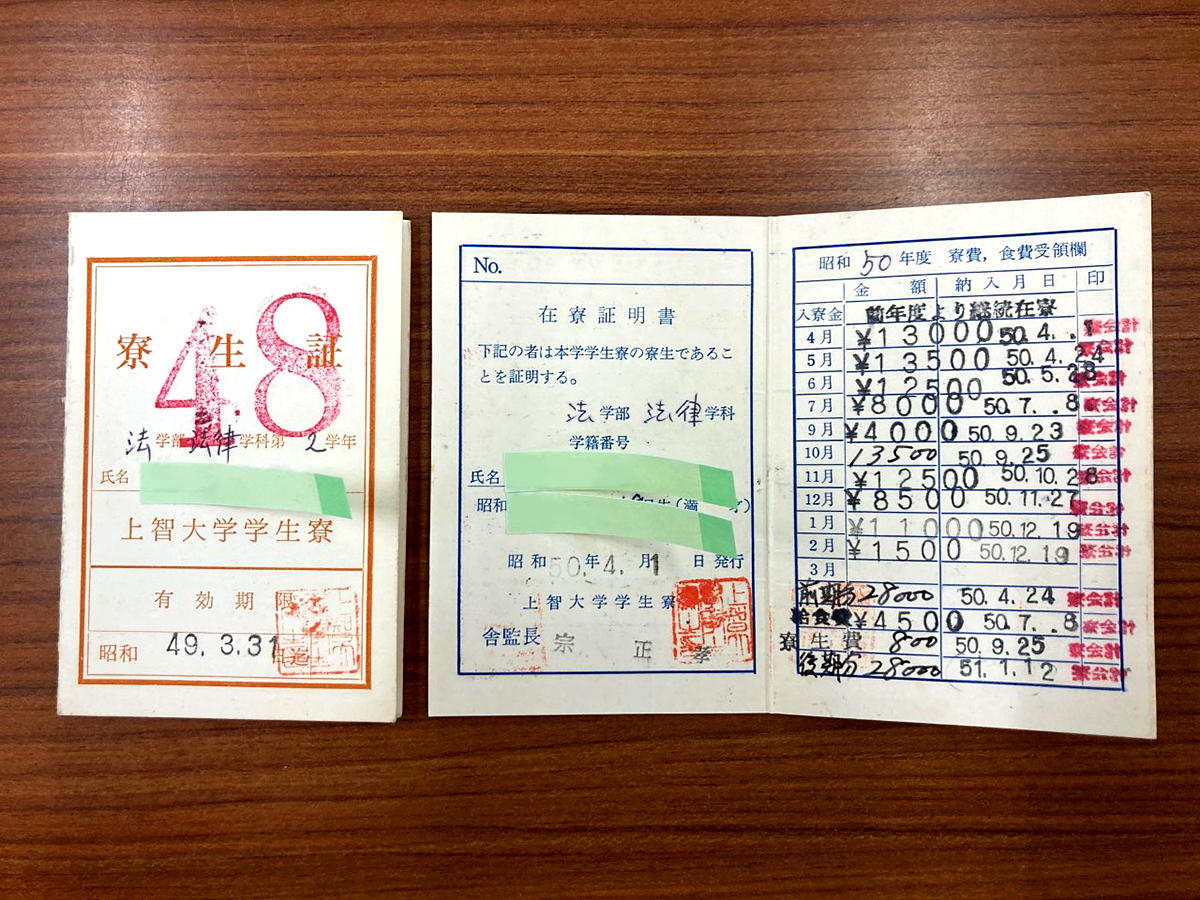

A resident’s card for the dormitory (donated by a former resident)

Document Number:donated by a former resident_13

A resident’s card for the dormitory (donated by a former resident)

Year-Round Schedule of Events at the Men’s Dormitory

March 30

Orientation Camp for New Residents

April 25

Spring Welcome Party for New Residents

April 29

Room Change Day

May 27

Parents’ Day

June 14

Spring Sports Event

June 20

Dormitory Festival

October 16

Fall Welcome Party for New Residents

November 8

Fall Sports Event

November 16

Dorm Cleaning Day

December 5

Disaster Drill

December 12-13

Christmas Party

January 14

Farewell Party for Leaving Residents

Document Number:Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

A welcome party for new dormitory residents

Document Number:Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

A welcome party for new dormitory residents

Document Number:Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

A sports event at the dormitory

Document Number:Student Dormitories_1_10th anniversary magazine

A sports event at the dormitory

3. The Beginning of Internationalization of the Student Dormitory

In 1971, Sophia University introduced an admissions system for foreign students wishing to study in Japan. In accordance with this move, in 1975, the men’s dormitory accepted for the first time five to six international students coming from the University of Wisconsin, with some conditions attached. With the subsequent increase in the number of exchange partners, the university formally set the “Guidelines on the Acceptance of International Students to the Student Dormitory” in July 1986. Following this guideline, the dormitory began accepting exchange students coming mainly from Sophia’s partner institutions. According to a history of the Sophia House men’s dormitory which appeared in the dormitory’s “Thirty-Fifth Anniversary Booklet,” that year marked “year one” in the internationalization of the student dormitory.

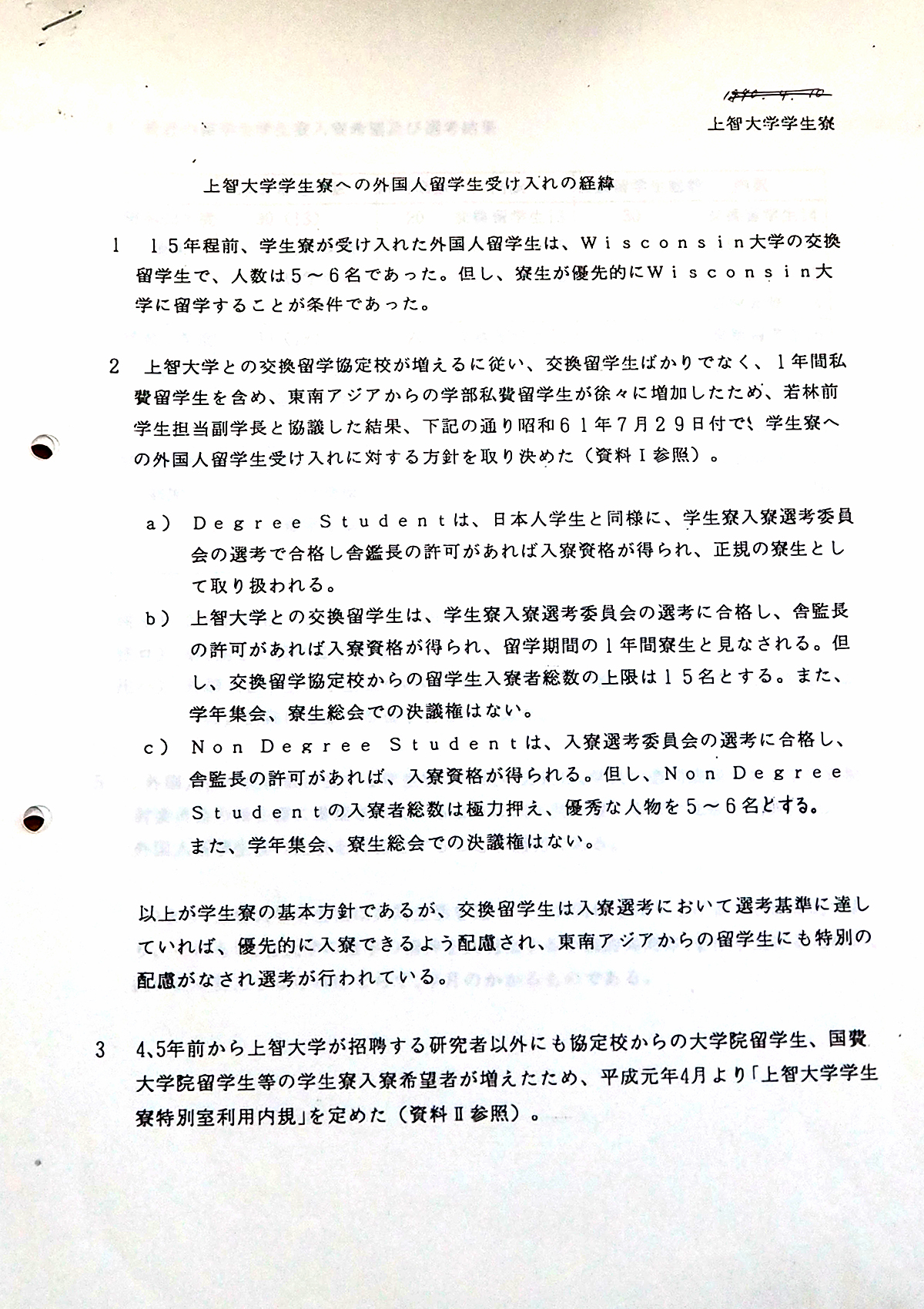

Document Number:Student Dormitories_10

A document explaining the dormitory’s policy on the acceptance of international students (1990)

Document Number:Student Dormitories_10

A document explaining the dormitory’s policy on the acceptance of international students (1990)

Shown on the left is a document written by a dormitory supervisor, and it explains how the dormitory came to officially accept international students from 1986. According to this document, as the number of exchange partners increased, international students of various categories coming to Sophia also increased. In response, dormitory supervisors consulted with the vice president of the university and set the “Guidelines on the Acceptance of International Students to the Student Dormitory” in July 1986. The key points of the “Guidelines” were as follows: 1. International degree students wishing to be admitted to the dormitory must go through the same applicant selection process that Japanese students go through. They will be treated as regular dormitory students once they are granted admission to the dormitory and receive approval from the head dormitory supervisor. 2. Exchange students wishing to be admitted to the dormitory must go through the same applicant selection process stated above. The maximum number of exchange students at the dormitory is set at fifteen. Exchange students are not entitled to vote at grade-level dorm meetings or at general dorm meetings. 3. Non-degree students wishing to be admitted to the dormitory will be subject to the same applicant selection process described in 1 and 2. Their number, however, is to be limited to the smallest possible number. With the university’s new policy of accepting more students from overseas, the student dormitory, too, entered a new era of internationalization.