Chapter 3

Toward a New Era

In the late 1980s and the 1990s, residents of the men’s dormitory kept searching for their own ideal vision for the dormitory, while adjusting themselves to the university’s decision to further strengthen its international character. In this process, an argument arose over the closing of the dormitory. Since 1983, when the Japanese government unveiled its “100,000 international student plan,” universities in Japan have worked hard at promoting internationalization. In “Higher Education in a Global Era,” a recommendation report submitted to the Ministry of Education in November 2000, the University Council of Japan (an advisory body to the Minister of Education) also stated that the acceptance of international students would result in increasing the international competitiveness of Japanese universities. The internationalization of higher education in Japan became inevitable. In January 2001, in response to changing situations, the Sophia School Corporation announced the “Grand Layout,” a long-range plan for the university’s future direction, and decided to close down Sophia House. This decision was taken as a part of the plan to improve the facilities on campus, including the building of appropriate venues for international conferences. As a result, the men’s dormitory at Sophia House closed in May 2005, and Sophia Edagawa Men’s Dormitory was opened off-campus in the same year. In 2012, the Faculty of Foreign Studies received a grant from the MEXT (the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology), whose purpose was to promote the development of “global human resources.” In this context, Sophia University took additional steps to meet the challenges of deepening internationalization. In addition to Edagawa Men’s Dormitory, the university opened Sophia Soshigaya International House in 2012, and Sophia Arrupe International Residence in 2019. This chapter presents the history of the Sophia House men’s dormitory from the late 1990s to its closure, using various materials including historical materials written by dormitory supervisors. We will also present some photos including those of the new dormitories currently in operation.

1. Searching for a New Vision for the Dormitory

Document Number:Student Dormitories_11

“Resolution of the Residents of the Sophia House Men’s Dormitory” (January 1987)

Document Number:Student Dormitories_11

“Resolution of the Residents of the Sophia House Men’s Dormitory” (January 1987)

On the “Resolution of the Residents of the Sophia House Men’s Dormitory”

The document on the left is the “Resolution of the Residents of the Sophia House Men’s Dormitory,” which was approved at an extraordinary general dorm meeting in January 1987. In November of the previous year, the dormitory supervisors conducted a survey on the raison d'être of the Sophia House men’s dormitory. Based on the result of the survey, the residents had a series of discussions at grade-level dorm meetings. The resolution adopted following these discussions expresses the residents’ determination to 1) improve their academic performance, 2) take active roles in various school-related activities, and 3) further strengthen communication among the residents. Notably, the residents stated that they would strive to further strengthen communication among the residents, given the growing number of international student residents. Although it is not clear why the survey was conducted, the document illustrates residents’ efforts to search for a new role in the context of the dawning era of internationalization.

Document Number:Student Dormitories_21

Document Number:Student Dormitories_21

Document Number:Student Dormitories_21

A memorabilia of Student Dormitories

Document Number:Student Dormitories_21

A memorabilia of Student Dormitories

Document Number:Student Dormitories_21

An explanation by the Dormitory supervisors about the future of the Dormitory (1988)

Document Number:Student Dormitories_21

An explanation by the Dormitory supervisors about the future of the Dormitory (1988)

In October 1987, the Sophia House men’s dormitory received a notice from the chancellor of Sophia School Corporation and the president of Sophia University stating that the Sophia School Corporation Board of Trustees had decided to close the men’s dormitory at the end of March 1991. The document on the left is an announcement to the residents from the dormitory supervisors on this matter. This was an unexpected decision for the supervisors, too. As they inquired of the Board of Trustees about the reason for this decision, they were instructed to set up a review committee on the Sophia House men’s dormitory, which was to investigate the current conditions of the dormitory, and to advise the chancellor and the president about its future. The review committee consisted of the dormitory supervisors and staff members of Sophia School Corporation. It met several times to discuss the dormitory’s raison d'être and how the dormitory should be run. By December 1988, the review committee submitted three reports to the chancellor and to the president. The document on the left mentions the contents of its interim report. In the report, the review committee argued that the Sophia House men’s dormitory should be maintained, not only for the benefit of economically disadvantaged students, but also as a place to implement Catholic education. The committee listed three reasons why the men’s dormitory should be kept in operation: 1. The dormitory embodies the spirit of Sophia University. 2. It is a place to foster outstanding individuals who can make important contributions to society. 3. It serves as a place to nurture leadership skills of individual residents. In the end, the men’s dormitory was not closed at the end of March 1991. But this was an event which posed anew the question of the role of student dormitories in the context of internationalization. Why did the university once again recognize the significance and the role of student dormitories at this point?

The document on the right is “A Suggestion Regarding the Internationalization of Universities in Japan,” a 1989 article by Tsuchida Masao, S.J., who was the president of Sophia University at the time. It was published in a newsletter issued by the Japan University Accreditation Association. In this article, President Tsuchida states that welcoming international students would contribute to the internationalization of universities in Japan. He makes the following remarks on the new role of student dormitories in an age of internationalization:

“With the increase in the number of international students, student dormitories have now assumed a new role. A dormitory where Japanese and international students live together can be quite beneficial in many ways.”

This passage provides us with some insights on why the university authorities came to appreciate once again the significance and the role of student dormitories.

Document Number:Student Dormitories_1

Memorial magazine produced every five years

Document Number:Student Dormitories_1

Memorial magazine produced every five years

Document Number:FC0024-011-004

“A Suggestion Regarding the Internationalization of Universities in Japan” (September 1989)

Document Number:FC0024-011-004

“A Suggestion Regarding the Internationalization of Universities in Japan” (September 1989)

Document Number:FC0083-003-008

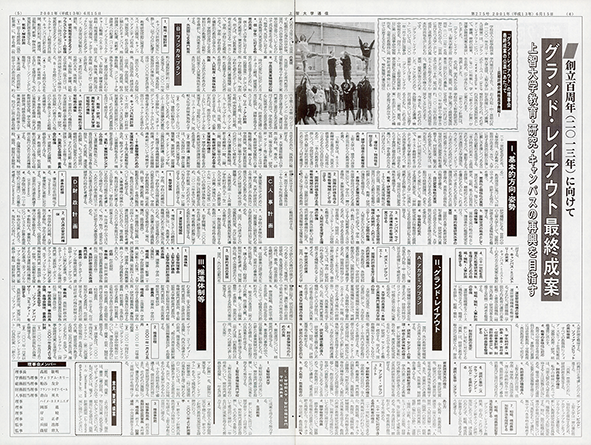

“Close yet Distant: The Sophia House Men’s Dormitory,” an article in the Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun (1992)

Document Number:FC0083-003-008

“Close yet Distant: The Sophia House Men’s Dormitory,” an article in the Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun (1992)

At the same time, some students at Sophia felt a sense of estrangement from the distinctive character of the Sophia House men’s dormitory. An article on the left is a special feature article which appeared in the student newspaper Jōchi Daigaku Shimbun. The title of this article is “Close yet Distant: The Sophia House Men’s Dormitory.” The author tries to clarify the reasons why the dormitory aroused in him a sense of estrangement. He explains in the introduction that the dormitory is physically “close” as it is located on campus, but it is “distant” because the dormitory students stick to a distinctive worldview and lifestyle, and because students who do not live there know little about how it operates. The author attempts to give as objective an assessment of the dormitory as possible by discussing the spirit of the dormitory and its governance structure as well as the voices of former residents who decided to leave the dormitory. What is interesting about this article is that the author, who was not a resident of the dormitory, regarded the dormitory residents as a group of people who carried on and further strengthened the spirit of “Sophia Family” passed down from their predecessors. Yet, from this article, it is also evident that the author could not fully erase the sense of estrangement. This is an important source material which reveals the feelings of non-resident students toward the Sophia House men’s dormitory.

2. Bidding Farewell to the Sophia House Men’s Dormitory

Stagnation in the economy as well as the decrease in the population of 18-year-olds posed serious challenges to Japanese higher education in the twenty-first century. Sophia was not an exception among Japanese universities in experiencing a downward trend in the number of applicants. On top of the demographic problem, the university faced other challenges such as the policy of higher education reform introduced by the MEXT, which called for accepting more international students, and for creating a more international educational environment suited to the new era of globalization. To respond to such multiple challenges, Sophia School Corporation Board of Trustees announced in 2001 the “Grand Layout,” a broad plan for the university’s future direction. The plan aimed to improve the campus facilities to help achieve the goal of excellence in education and research by the university’s centennial anniversary in 2013.

Document Number:Jōchi Daigaku Tsūshin June 2001

Jōchi Daigaku Tsūshin newspaper reporting on the Grand Layout (June 2001)

Document Number:Jōchi Daigaku Tsūshin June 2001

Jōchi Daigaku Tsūshin newspaper reporting on the Grand Layout (June 2001)

On the left is an issue of Sophia’s internal newspaper, Jōchi Daigaku Tsūshin, reporting on the details of the “Grand Layout.” According to the Grand Layout, aging Sophia House was to be demolished and a new building was to be erected on the same plot. A new dormitory was to be built off campus, but the Sophia House men’s dormitory was to be closed down. Unfortunately, no documents exist which tell us how the residents reacted to the news that the dormitory was to be closed down. Dormitory residents used to publish commemorative booklets on the occasion of the dormitory’s major anniversary celebrations. In the final, “Forty-Fifth Anniversary Booklet,” published in 2002, a detailed timeline of Sophia student dormitories from the time of St. Aloysius Hall was included. How did the residents feel as they looked back on the history of student dormitories at Sophia?

Document Number:November 20st 2004_ closing of the Sophia House men’s dormitory6206

A Mass held to commemorate the closing of the Sophia House men’s dormitory (Auditorium, Building No. 10)

Document Number:November 20st 2004_ closing of the Sophia House men’s dormitory6206

A Mass held to commemorate the closing of the Sophia House men’s dormitory (Auditorium, Building No. 10)

Document Number:November 20st 2004_closing of the Sophia House men’s dormitory6372

he last head supervisor Kida Isao, S.J. speaking at a party to commemorate the closing of the dormitory (Akasaka Prince Hotel)

Document Number:November 20st 2004_closing of the Sophia House men’s dormitory6372

he last head supervisor Kida Isao, S.J. speaking at a party to commemorate the closing of the dormitory (Akasaka Prince Hotel)

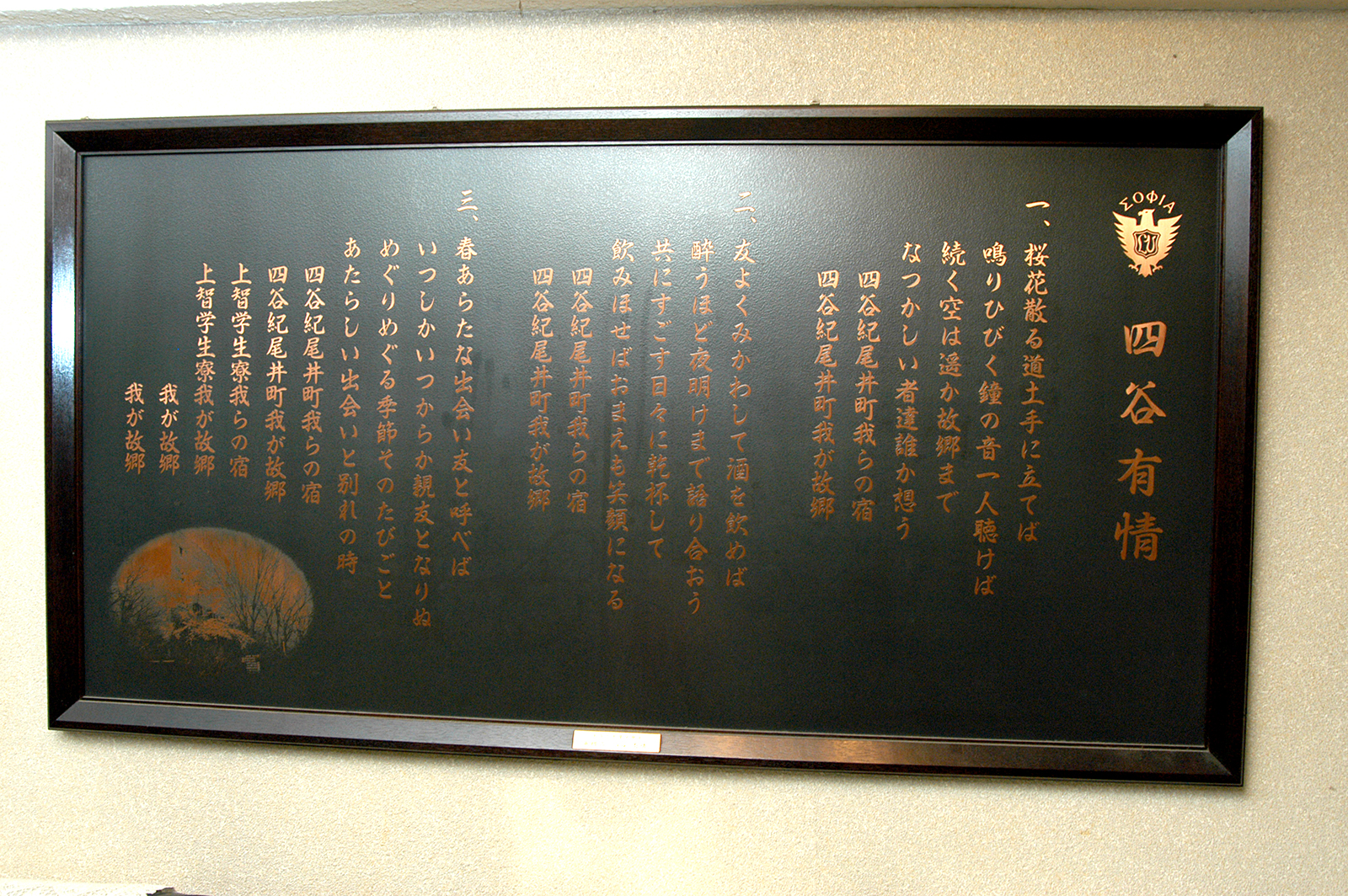

Document Number:kanban. fudarui_2

A plaque with the lyrics of the dormitory song “Yotsuya Ujō,” originally hung on the walls of the lobby of the Sophia House men’s dormitory (dimensions (cm): approximately 82x162x4.1; a gift from dormitory graduates of 1994)

Document Number:kanban. fudarui_2

A plaque with the lyrics of the dormitory song “Yotsuya Ujō,” originally hung on the walls of the lobby of the Sophia House men’s dormitory (dimensions (cm): approximately 82x162x4.1; a gift from dormitory graduates of 1994)Audio recording of “Yotsuya Ujō” (words and music, arrangement, performance, and singing by Ugata Masato, 2021)

※Please click to play

Sophia House closed down in 2005. The university held a Mass and a farewell party in November of the same year to commemorate the closing of the facility. Shown on the left is a plaque with the lyrics of the dormitory song “Yotsuya Ujō,” (Yotsuya, the Home of Our Heart), which used to hang on the wall in the lobby; it is now preserved at Sophia Archives. The song was adopted as the dormitory song as the result of a song competition held at a dormitory anniversary event. Click the button below the photo of the plaque to play “Yotsuya Ujō.” The audio source was provided by the composer of the lyrics and the music, Mr. Ugata Masato, (Class of 1983, Faculty of Law, Department of Law). According to Mr. Ugata, the first verse of the song depicts the scenery of Yotsuya in the daytime, the second verse portrays Yotsuya at night, while the third verse evokes an image of four-year college life, seen from the viewpoint of a dormitory resident. In April 2017, Building No. 6 (Sophia Tower) opened at the former site of Sophia House.

3. Student Dormitories in Operation Today

Sophia Edagawa Men’s Dormitory (Completed in 2005)

Document Number:2005.03.14_Sophia Edagawa Men’s Dormitory_8060

Sophia Edagawa Men’s Dormitory (Completed in 2005)

Document Number:2005.03.14_Sophia Edagawa Men’s Dormitory_8060

As a substitute for the former men’s dormitory, Sophia Edagawa Men’s Dormitory was opened in Edagawa, Kōtō Ward, Tokyo. Each room in the dormitory is designed as one-room apartment with a mini-kitchen to provide residents with their own private space.

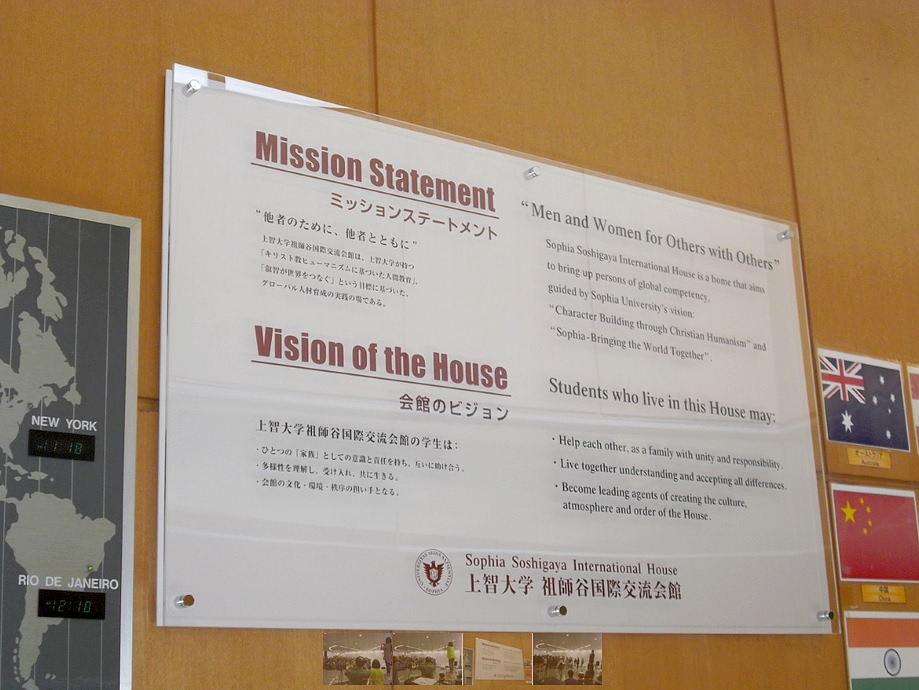

Sophia Soshigaya International House (2012)

Document Number:100 Years of Student Dormitories_Sophia Soshigaya International House2_20140507

Sophia Soshigaya International House (2012)

Document Number:100 Years of Student Dormitories_Sophia Soshigaya International House2_20140507

In April 2012, another dormitory, Sophia Soshigaya International House, began its operation. This dormitory is run in accordance with the university’s educational principles as stated in the “Mission Statement” and the “Vision of the House.” It offers an excellent environment for bringing up persons with global competency. The mission statement of the dormitory refers to slogans such as “character building through Christian humanism” and “Sophia - Bringing the World Together,” which attest to the continuity in the tradition of Sophia dormitories going back to the days of St. Aloysius Hall.

A plaque with the “Mission Statement” of the Sophia Soshigaya International House, hung on the lobby walls

Document Number:100 Years of Student Dormitories_A plaque with the “Mission Statement” of the Sophia Soshigaya International House_20140507 Sophia-Arrupe International Residence (2019)

Document Number:February 21st 2019 Sophia-Arrupe International Residence_8146

Sophia-Arrupe International Residence (2019)

Document Number:February 21st 2019 Sophia-Arrupe International Residence_8146

From April 2019, Sophia University also began operating Sophia-Arrupe International Residence in Shinanomachi, Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo. The name of this dormitory is adopted from Father Pedro Aruppe, S.J. (1907-1983), a former Superior-General of the Society of Jesus whose ideas are intimately linked with Sophia’s educational vision. What distinguishes this dormitory is that its “Vision” lists as an important objective “developing the residents’ capacity to play a leadership role in today’s globalized society.”

A statue of Father Pedro Aruppe, S.J.

A statue of Father Pedro Aruppe, S.J.(Sophia campus, in front of the Kulturheim) Document Number:100 Years of Student Dormitories_A statue of Father Pedro Aruppe2_20210713